|

Non-linear Life

|

|

Alan Turing job was at Manchester University, but he didn't live in Manchester. He had a semi-detached house in the outskirts of Wilmslow, fifteen kilometres south of Manchester in the Cheshire countryside. Modern streetmap here.

He continued training for long-distance running. In 1951 he met a 17-year-old Manchester Grammar School sixth-former, Alan Garner, who was also running in the roads round Wilmslow and Alderley Edge. They trained together in the evenings, two or three times a week. Alan Garner later became a well-known author. In 2011 he wrote of My Hero: Alan Turing.

They had both seen that first Technicolor feature film in 1938, and Alan Garner too was haunted by the symbolism of the famous poisoned apple.

|

|

|

Alan Turing led a life of his own. Besides the long-distance running, he was running a long-distance relationship with Neville Johnson, whom he had met in Cambridge, but was now too far away as an electronic engineer in Reading.

He opened the second half of the twentieth century with his own, completely original, mathematical theory of morphogenesis: the theory of biological growth. His work contributed to the huge field of

non-linear systems as well being as pioneering work in mathematical biology.

Turing's working and writing was closely focussed on explaining specific biological phenomena. His idea was that non-linear partial differential equations could describe and explain the development of an initially homogeneous mixture of chemicals into the asymmetrical forms seen in biological structures.

Such equations could only be attacked by numerical methods and so demanded the use of a computer.

|

A personal computer

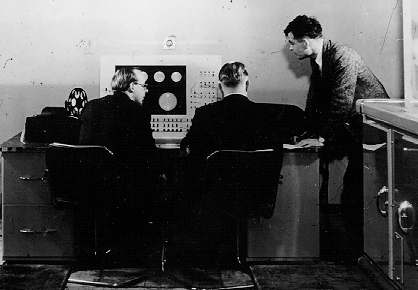

As described on another Scrapbook page, Manchester University had the world's first working computer in 1948. In February 1951 a fully engineered version, the Ferranti Mark 1, came into operation.

The result was that Alan Turing was in the one place in the world where he could enjoy the personal use of a computer to work on his new theory of life.

|

The engineers at Manchester had triumphed through finding a way to use cathode ray tubes as its fast storage system. There was a slower magnetic drum as well — ancestor of the hard disk.

The screen of the tube actually was the storage system itself, and the fact that it gave a visual display was regarded as incidental. Other people disapproved of 'peeping' at the progress of the program. But Turing liked watching what was happening in his calculations. So, ahead of his time as usual, he became the first to be glued to a screen as a computer graphics user.

|

|

A hard place

The Computer Laboratory at Manchester remained dominated by the hardware skills of the electronic engineers, and after 1950 Alan Turing lost interest in the field of what was to become computer science. He never revived his early ideas for developing computer languages. He wrote machine code in base-32 arithmetic for his own work.

|

Culture clash: the soft machine in a hard place.

|

|

Behind the Scenes

Besides being used for the frantic atomic bomb programme, which culminated in the British test of October 1952, a copy of the Manchester machine went to

GCHQ, successor to the Bletchley Park organisation. It was based at Eastcote in north-west London until moving to Cheltenham in 1952. After 1948 Turing was consulted, possibly on some aspect of the Venona problem of decrypting Soviet traffic. This appears to have been the dominant Anglo-American priority of the time, and played an important role in identifying Soviet agents. It seems very likely that Turing did some work on the Manchester computer for GCHQ. The engineers were surprised when he specified the need for a 'sideways adder' in the hardware, and this may well have been with codebreaking in mind.

|

Breaking the Codebook of Nature

| |

Turing's morphogenesis work was largely unpublished in his lifetime.

|

|

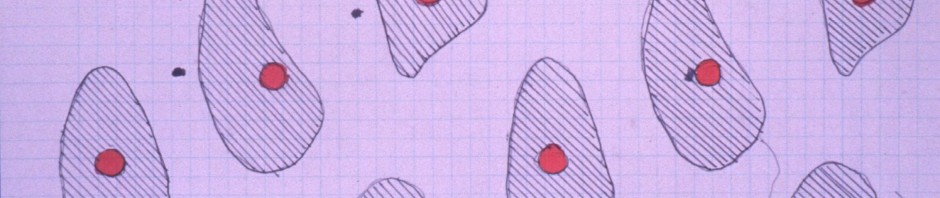

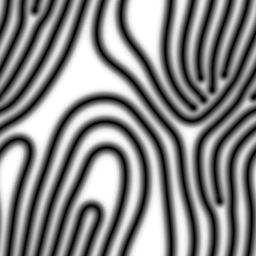

Suprisingly complex structures arise out of very simple reaction-diffusion equations — that is the essence of Alan Turing's idea.

Alan Turing's programme for mathematical biology was so far ahead that only in the 1980s did computers really become fast enough to do justice to what he had in mind.

The Xmorphia project was an on-line classic of the 1990s. It has been reincarnated here.

When I started this website in 1995 you needed a supercomputer to generate these pictures, but now as

this page explains, a laptop can implement the equations, which were essentially those Turing wrote down.

The equations can be solved on a torus, thus generating a tiling. Roy Williams and Bruce Sears, who created the Xmorphia site, set up a page for just this purpose, called

The Wallpaper Machine. I used it for papering the pages of the short Turing biography on this site.

|

|

|

Nowadays there are very many research groups studying such reaction-diffusion systems and other ideas flowing from Turing's work. One such is

Philip Maini's research group site at Oxford University.

Go to 'Research gallery' then to 'Pattern formation' and 'The mechanochemical theory of morphogenesis.'

Video of Philip Maini on 'Turing's Theory of Developmental Pattern Formation'

|

Fifty Years Ahead

Turing's models were taken up the 1970s and developed with increasing computer power, but what he really wanted to show was that these models gave a correct scientific account of what has happening in biological growth. This has had to wait even longer.

|

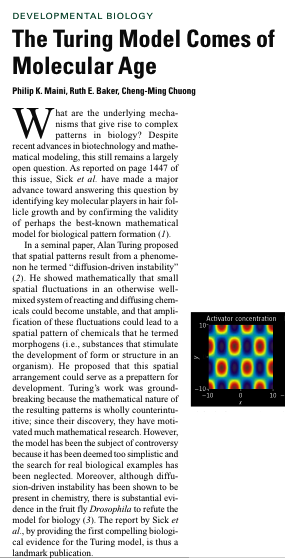

| In the journal Science, 1 December 2006, a European group of biological researchers (Stefanie Sick, Stefan Reinker, Jens Timmer, Thomas Schlake) found the first direct physical evidence for Turing's theory of pattern formation.

An accompanying paper by Philip Maini and his collaborators (opening paragraph shown at left) explains the significance of their discovery, which came 55 years after Turing's paper was submitted.

| How the Zebra got its Stripes

By 2014, further indication of the physical reality of Turing's chemical mechanism had been found. This is explained and reviewed in a substantial article from the Wellcome Trust here with extra material here and here.

The article has an interesting quotation from Francis Crick, one of the co-discoverers of DNA structure. Turing's theory was complementary to the DNA question and it is a rather odd fact that he made no reference to it. |

Alan Mathison Turing, FRSIn July 1951 Alan Turing was elected to a Fellowship of the Royal Society, the main scientific academy of the United Kingdom. He had almost become respectable at last, at 39, and sat for formal portrait photographs. On 9 November 1951 he submitted his paper on morphogenesis to the Royal Society. |  |

|

In December 1951, Alan Turing met a 19-year-old man at a spot in Oxford Street, Manchester, which was a very short distance from his University base.

Manchester is now a lively city with a huge student population and a big gay scene, immortalised in 1999 in the TV drama series

Queer as Folk. It was very different in 1951, but Turing could not have failed to notice what was, even then, the most notable meeting-place for gay men in the North of England. It was right on his doorstep.

As usual, Alan Turing walked into another culture clash, this time the most dramatic of all.

|

The outward appearance of the area had not changed much in 2001 (my photo). |

|

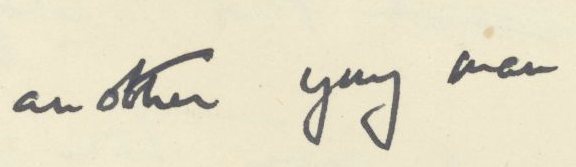

Alan Turing was aware of the drama of it: it began as a classic case of the early 1950s in which arrests of gay men were sharply increasing. Later he wrote a short story, a light fictionalisation of the pick-up. See the surviving pages of manuscript.

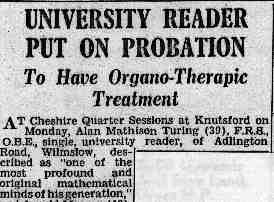

A complicated sequence of events developed, told in Alan Turing: the Enigma, and subsequently dramatised in the play Breaking the Code. (This actually used Turing's own fictionalisation.) YouTube of the television version. It resulted in them both being arrested on 7 February 1952, the day of Queen Elizabeth's accession. Their crime — three occasions of consenting sex in Alan Turing's house in Wilmslow. The trial, at Knutsford, Cheshire, followed on 31 March 1952.

|

Surprisingly, for 1952, he used the expression 'another gay man' in his story. |

|

| From the local newspaper, the Alderley Edge and Wilmslow Advertiser, 4 April 1952. |

|

See the official record of the charges and sentences.

It was argued in court that the importance of his research work meant he could be allowed to take injections of oestrogen as a scientific alternative to a prison sentence. This concession — chemical castration — was called

'organo-therapic treatment'. It had to continue for a year.

He was reported as protesting to the police that a 'Royal Commission was sitting to legalise it.' If so, he was mistaken. The Wolfenden commission was not set up until 1954. Even when English law was changed in 1967, what Alan Turing had done remained a crime. The 'age of consent' was set at 21, and was only changed to 18 in 1994.

Behind the scenes, there was the question of Turing's secret work for

GCHQ. Now he was revealed as a homosexual and so automatically a 'security risk' by post-war Anglo-American standards.

|

In 2001 a memorial sculpture of Alan Turing was unveiled in the park near to the Manchester pick-up scene. This is the sculptor, Glyn Hughes. |

The concept of homosexuals as 'security risks' only changed in the 1990s.

GCHQ is now part of the Stonewall Diversity Champions Programme. See their 2014 workshop on discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation, based on the Alan Turing story.

It was utterly different in 1952: Alan Turing's revealed homosexuality was almost the worst thing in the world, an unspeakable and terrifying issue of national security.

|

Myself at the same event, 23 June 2001. |

Sixty years later

These events traumatised everyone involved. No-one spoke out; there was public silence. I learned of them in 1973, from some of the very few people who knew something of them, and in 1977 I embarked on the full-scale biography of Alan Turing in an attempt to do full justice to what had happened.

Although the story featured centrally in Hugh Whitemore's 1986 play, and so reached a wide public, it was not seen a mainstream issue. But after 1997, the new Labour government lent unequivocal support for equality on grounds of sexual orientation. An early aspect of this came in 1998 when

when Chris Smith, a prominent government minister, made a public statement that 'Alan Turing did more for his country and for the future of science than almost anyone. He was dishonourably persecuted during his life; today let us wipe that national shame clean by honouring him properly.'

After 2000, with the principle established, many more people felt a shock that such a thing could ever have happened. In 2009 a British computer scientist, John Graham-Cumming, started a petition on the webspace set up by the British government, calling on the Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, to apologise for the prosecution in 1952.

It gained wide support, with Richard Dawkins a notable contributor. The Independent newspaper, with more letters here, and BBC News, gave sympathetic coverage. Strong grass-roots support came from Manchester, but calls for signatures appeared in media from logicians' messageboards to gay sex chatlines. Notably, this was a campaign in which the computer itself, facilitating new social media, was a key aspect.

On 10 September 2009, the Prime Minister responded with a full personal statement of apology.

The statement went further and deeper than the petition asked for, making it clear that Alan Turing's prosecution and punishment was only one aspect of the law which had blighted millions of lives. It also linked the development of European culture since 1945 with the success of Alan Turing's war work.

After 2009 there were further developments: see

the Parliamentary debate, 27 June 2012, on the occasion of the centenary. Generally, the international attention paid to a Prime Minister's statement did much to raise awareness of Alan Turing's life and work.

Many petitioners thought that the apology did not go far enough, and a legal 'pardon' was called for. The 2012 centenary amplified this thought. On 14 December 2012 eleven distinguished people, including Stephen Hawking, called for a `pardon' as a special exceptional act.

The public debate around this question brought in principles of doing justice across historical periods, Turing's various claims to a distinctive status both in science and service to the state, and the question of whether it was justifiable to demand special treatment for an individual.

Two articles (1), (2) describe the background of the thousands of other similar prosecutions.

Two legal opinions (1),

(2) offer opposed views on legal pardons.

Another argument, from

a scientific perspective, is in line with a number of other comments, including my own in an article in Nature, to the effect that it was the British state that needed to be pardoned, not Turing.

Additionally (1) there is a difficulty about arguments which amount to pulling rank: in other contexts it is thought very wrong that status should imply immunity from prosecution and (2) rather than perform a symbolic act, the government could better advance truth and reconciliation by revealing the secret papers from 1952-54 relating to Turing's security status.

But from a different angle, many people argued that it was better to demand first a pardon for Turing, and then use this precedent to extend it to all the victims of the law. This line was taken up powerfully by

my friends Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe, the Pet Shop Boys, who took advantage of their leading position in the 2012 Olympic ceremony to lobby the Prime Minister, David Cameron.

|

|

The government acceded to the demand, and on 24 December 2013 issued a formal Royal Pardon (actually an executive act of the Justice Secretary). See a copy of the legal document. See The Guardian, which notes my reaction, with other somewhat negative comments

(1), (2), (3) on the day. But this was generally regarded as a triumph of the Turing Centenary events: some ecstatic reactions were as if history itself had been changed.

Gordon Brown spoke the words of his Apology and the BBC Chorus sang the medieval words of the Pardon in an extraordinary Promenade concert of 23 July 2014. The musical art of the Pet Shop Boys transcended logical arguments about justice and gave perfect voice, at the heart of British national life, to an overwhelming feeling that this jagged wound in history must be addressed.

Lord Sharkey quoted my words in Parliament, 21 July 2014 but without effect; there is no immediate prospect of the pardon being extended to all similar cases. But the story isn't over yet.

|

A Man from the Future:

Alan Turing's life celebrated at the Royal Albert Hall,

23 July 2014 |

Alan Turing's reaction?In summer 1952, a holiday in Norway.

|

|

|